Our Virtual Tour Of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert

Khamariin Khiid Monastery

June 22, 2020

Taking The Trans-Mongolian Train – Your Introduction

July 15, 2020Our Virtual Tour Of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert

“Mongolia’s Gobi Desert seems like earth reduced to its most basic elements: rock, sky, glaring sunlight and little else. The apparent emptiness is both compelling and intimidating. But the Gobi is not empty; it is filled with space, sky, history and landscapes.” Conservation Ink

The Gobi Desert spans southern Mongolia and northeast China and is the world’s fifth-largest desert. Five of Mongolia’s provinces form the Gobi in Mongolia – Omnogobi, Dorngobi, Dundgobi, Bayankhongor and Gobi Altai. It is a fossil-rich mid-latitude desert and the geology of the region has resulted in rich mineral wealth with immense copper, coal, and gold reserves all found throughout the Gobi. Modern life is making an impact, with new rail and road transport links connecting some of Mongolia’s largest mines such as Rio Tinto to the border with China.

The interactive map below is not the ultimate list but it shows some ideas based on 15 years of living and working in Mongolia and from our ongoing research. Traditionally, all journeys go in a clockwise direction in Mongolia, so this one does as well.

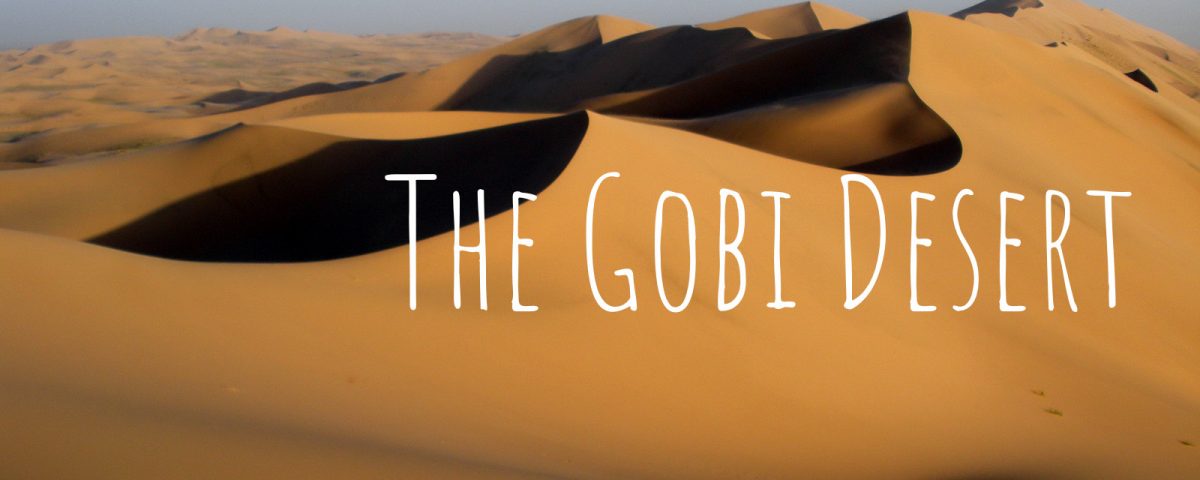

The climate is extreme and precipitation averages less than 100mm annually (the Gobi is a rain shadow desert formed by the Himalaya range blocking rain-carrying clouds from reaching the Gobi from the Indian Ocean). However, the soil in the Gobi is not necessarily barren – it is only made so by the lack of rain. With moisture, the Gobi blooms – it becomes a green desert. The diversity of the region provides habitat for many of Mongolia’s threatened species, including the wild camel, Gobi bear, wild ass and snow leopards (yes, snow leopards). It also provides a home for a variety of rodents including species of hamster, jerboa, gerbils and the (extremely cute) Mongolian Pika.

Dust storms such as this one are a frequent occurrence in Mongolia especially during the spring season – not just in the Gobi Desert but countrywide. Dust storms are called ugalz and are quick, violent and short-lived and last a couple of hours or less.

Desert flora has adapted to the extremes of heat and aridity by using both physical and behavioural mechanisms, much like desert animals. The plants and water together help to sustain the domesticated livestock and the wild animals in their natural habitats.

‘The word gobi denotes a desert or a waterless place but doesn’t really mean anything by itself. The Mongolians have many descriptive words for types of gobi, like the Eskimo and Scandinavians with their words for snow. There are supposed to be thirty-three Mongolian words for gobi – such as gravel, sand, bare earth, rock, mountain, dune, watering place, and those describing various types of vegetation. The ancient Gobi was more like an East African savannah – long grasses and some trees, with lakes and marshes. Successive waves of drought turned it into the more barren land it is today.’ John Man, Tracking The Gobi

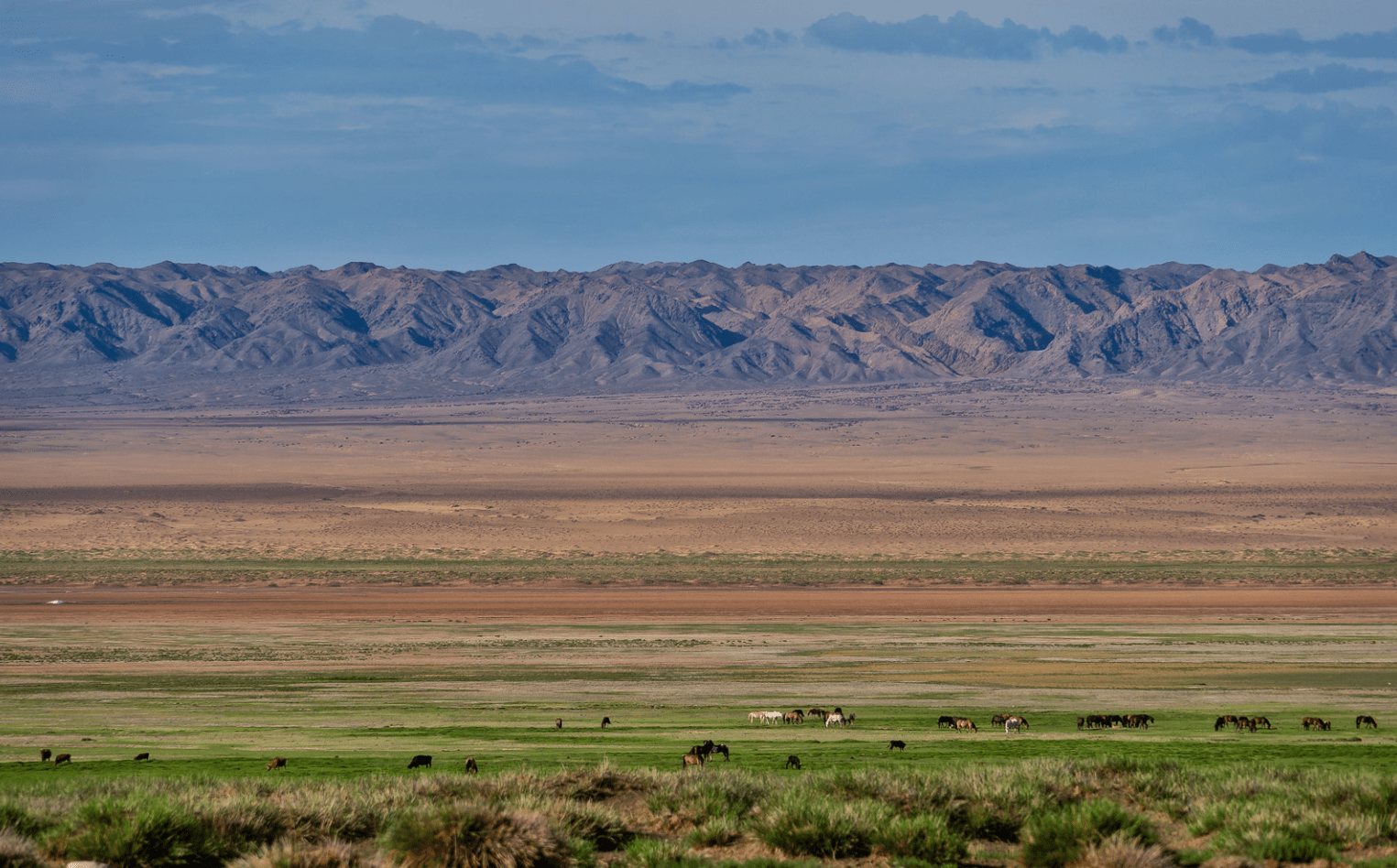

Alpine Mountains & Gorges

You will find fracture zones running along the base of the mountains – sometimes visible as a contour. These fracture zones dominate the ecology and economy of the Gobi as along these lines subterranean water is squeezed to the surface. Not all rainfall evaporates – some replenish the water table which under subterranean pressure then squeezes up through the cracks, emerging in springs.

One area where you can find a series of springs is the interior of the Gobi Gurvan Saikhan National Park – Mongolia’s largest national park and a mountainous terrain rising out of the extensive desert plains and a region of incredible biological diversity. This mountainous region was formed by the same tectonic activity that created the Himalayas and is part of the Gobi Altai Range – the outer crumple zone of the Himalayan geological activity.

Yolyn Am is one such spring in Gobi Gurvan Saikhan – meaning Vultures Gorge/Mouth/Canyon it takes its name for the Lammergeier’s (Bearded Vultures) that you may see circling on the thermals. It is renowned for its sheet of ice several meters thick that forms during the winter in the narrow defile (often preserved until early July as the overshadowing peaks of Yolyn Am ensure a slow melt). The water tables beneath the Gobi Gurvan Saikhan were laid down by ancient processes – when the mountains began to lift, and fault lines cracked open, water squeezed up from below sought the easiest route downhill.

Dinosaurs & Bad-Ass Explorers

‘The Gobi offers a cross-section of this sweep of earth’s history.’ – John Man

The Gobi provides a lesson in the changing nature of Earth’s environment – it has not always been a desert. 80 million years ago (the Late Cretaceous Period), it was a landscape of open grasslands – a savannah type landscape, there were marshes, lakes, rivers and areas of forest. The Late Cretaceous Period was the last stage of dinosaur dominance and the most notable fossil finds came from the Nemegt Basin. Fossils include species that bridge the transition between the age of the dinosaurs and the age of mammals.

Jess: When was the Gobi a sea? Turuu: Back when I was a fish.

It is said that Stephen Speilberg based the character Indiana Jones on Roy Chapman Andrews. In the 1920s, Central Asia was little known scientifically. Andrews and a group of scientists explored the region during a series of five ‘Central Asiatic Expeditions’ in the 1920s – working for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Henry Fairfield Osborn, the boss of Andrews, had predicted that ‘Asia would prove to be the womb in which mammals had developed, and the base from which they dispersed throughout the world.’ (John Man: Gobi: Tracking the Desert). Andrews’s expeditions to the Gobi remain significant for, among other discoveries, their finds of the first nests of dinosaur eggs at Bayanzag (The Flaming Cliffs), new species of dinosaurs, and the fossils of early mammals that co-existed with dinosaurs.

‘I have been so thirsty that my tongue swelled out of my mouth. I have ploughed my way through a blizzard at 50 below zero, against wind that cut like a white-hot brand. I have seen my whole camp swept from the face of the desert like a dry leaf by a whirling sandstorm. I have fought with Chinese bandits. But these things are all part of a day’s work.’ This Business Of Exploring, Roy Chapman Andrews

Mongolia’s Flaming Cliffs – also known as Bayanzag.

Camels & The Singing Sands

And you can’t discuss the Gobi Desert without mentioning camels … of the two-humped kind. Although most of the Bactrian camels in Mongolia are domestic, there is a small population of wild camels (Camelus ferus) that live in three separate habitats throughout the Gobi Desert (with a Mongolian population of roughly 350).

Camels are perfect for the desert because:

- Their pale colour is better for reflecting the sun’s rays

- They have two pairs of eyelashes that are extra long – designed to keep out the sand.

- They have tough teeth for chewing the thorniest desert plants.

- They have thin stomach hair – which lets the heat escape from the camel’s body.

- The long legs help to hold the camel off the ground where the air is cooler.

You’ll find camels throughout the country including at Khongoryn Els – Mongolia’s highest dunes. The range is known locally as Duut Mankhan – the singing sands although the sands mostly sing when the wind blows from the east to the west – when the grains of sand with a layer of silica is set moving by the wind, vibrating together to make a deep hum. The sand dunes stretch for about 180km long and 12km wide in a valley squeezed between the Bayan Tsagaan Mountains to the north and the Zoolon and Sevrey Mountains on the south. The highest dunes rise around 200m from the valley floor and occur near the north-western end of the dune field.

The sand dunes are breached by a natural highway of low-lying sand and this north-south route has been in use for centuries. The prevailing winds blow away lightweight sand before it has a chance to lay down in deep drifts thereby preserving the route.

What you might not know is that camels have been used for transportation purposes in Mongolia for centuries including carrying on The Tea Road. You can learn more about our camel trekking experiences here.

Life In The Gobi’s Extremities

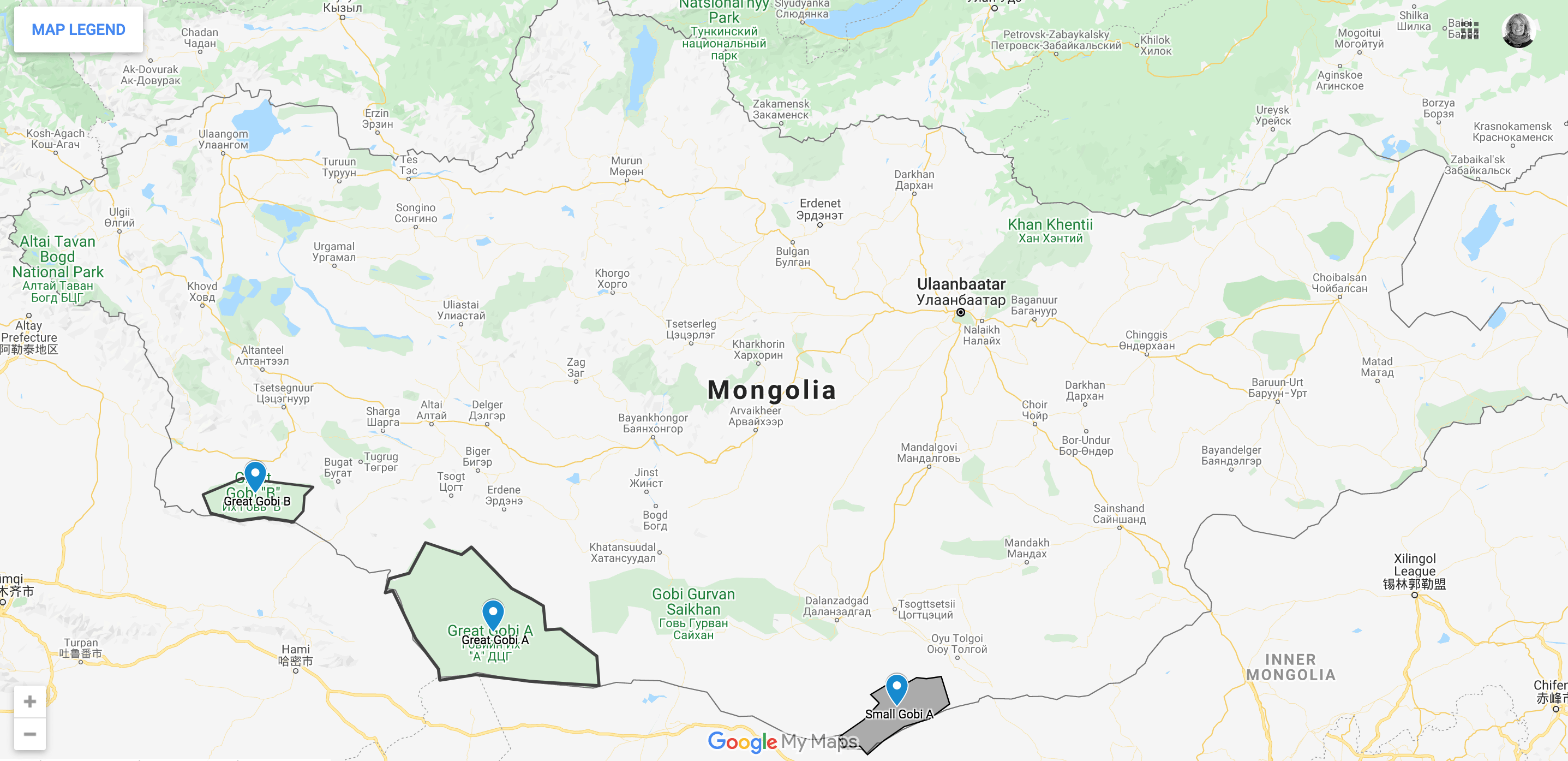

The Gobi is an extreme environment and one of the most extreme locations within it is the Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area in the south-west of the country. This mass of land is divided into two separate parts – part ‘A’ of Great Gobi SPA spans five districts of Bayankhongor Province and Part ‘B’ covers four districts of Khovd and Govi-Altai Province. There is also a Small Gobi ‘A’ and ‘B’ which represents the main characteristics of southeastern Gobi – including saxaul forest (the saxaul plant is found either as a small tree or as a large shrub with heavy, coarse wood and spongy, water-soaked bark) and the natural habitat of the endemic khulan (wild ass). The Great and Small Gobi SPA was established to conserve an integral part of the Central Asian desert ecosystem. Despite the harsh environment, the protected area hosts an exceptional representation of some of Mongolia’s most rare and critically endangered species as well being a site of large- scale animal migrations. Endangered species include the Snow leopard (Uncia uncia), Ibex (Capra sibirica), Argali sheep (Ovis ammon), Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica mongolica), Gobi bear (Ursus arctos gobiensis) and wild Bactrian camel (khavtgai – Camelus ferus bactrianus). The Przewalski horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), which was ultimately extinct in the wild, has been reintroduced to the Takhiin Tal reserve.

Energy Centres

True, when you think of the Gobi Desert, energy centres may not immediately come to mind. However, Khamariin Khiid Monastery – established in the 1830s by Danzan Ravjaa, a revered figure in Mongolia although little known in the West – is an important spiritual centre – a monastery as well as a place of pilgrimage for Mongolians and followers of Buddhism. Mongolians focus on the energy centre known as Shambala (a legendary kingdom located in Central Asia, but whose precise place remains unknown. It’s a quiet place, where all the inhabitants could live in joy and harmony. Mongolian people think that the entry to this kingdom is at the monastery). Learn more – https://www.eternal-landscapes.co.uk/khamariin-khiid-monastery/

If you’ve enjoyed exploring the Gobi Desert with us why not look at the other locations in our series of virtual tours – https://www.eternal-landscapes.co.uk/mongolia-introduced-a-virtual-tour/ and https://www.eternal-landscapes.co.uk/virtual-tour-eastern-mongolia/. Alternatively, explore the Gobi Desert through the words of authors, EL guests, a US-based non-profit organisation and a few 20th-century explorers – https://www.eternal-landscapes.co.uk/gobi-desert-mongolia/. And if you’re interested in exploring the Gobi Desert with us then take a look at our Gobi Desert Explorer private tailor-made experience.

Jess @ Eternal Landscapes